As we take off for Vienna in the late summer, I think of a native-Berliner friend, who hates Berlin in the way that perhaps only a native can hate his home town. He loves Vienna. What a city! he says. What charm! What elegance! (Charm is not a quality Berlin is often accused of; it tends to cultivate a Chicago-like roughness.)

I like Berlin, and there's a kind of traditional Viennese charm I don't like. Operettas and Strauss waltzes and other cheap lightweight art, half-screening the rampant militarism and authoritarianism and political anti-Semitism that flourished in the old Austria. (Hitler was an Austrian, folks: he wasn't a Prussian. Vienna was where he learned to make anti-Semitism a political tool.) A kind of sentimental fakery lingers in the air: Hermann Broch, writing about late-nineteenth-century Vienna, called it the metropolis of kitsch.

But things change, things change. The kitsch hasn't vanished, but things change. The first time I was in Vienna was more than forty years ago, and it was a sad sooty hulk then, peopled with war widows in saggy stockings. Grimy palaces and institutional buildings lined the Ringstrasse, thick and indigestible as stuck-together dumplings. I heard people refer to a building as the War Ministry which hadn't been the War Ministry since 1919 or so. It was as if the life of the city had been sucked backward into some black-and-white photo of the past.

|

| Vienna State Opera, ca. 1898. Photo from Wiki Commons. |

Of course all the cities were black with coal smoke then. I thought the stone in Europe was naturally some dark color, like the granites and sandstones of the American West.

But when Europe started to wash its face and ban coal fires, back when we were young, I was amazed. I hardly knew that stone came in these colors, it didn't seem like stone. Cream or honey colors, or spring-rain colors. Sometimes bright-white, milk-in-the-sunshine white.

Now we are old the and the city is young: the widows in their clumpy shoes are gone to their long repose, the streets are full of young persons who are probably developing business plans; and the washed white buildings are hung with flowers.

|

| Corner of Burggasse and Stiftgasse, Vienna, August 2017. Photo, M. Seadle |

Archangel and I stayed in an apartment just around the corner from this place, in Vienna's Seventh District. More precisely, we were in Spittelberg, a recently renovated neighborhood (the renovations have made less public room for cars, and more for little garden spaces where people rock baby carriages back and forth under the trees, more room for the jumble of restaurant tables that spills out onto the sloping, stony street). The neighborhood is on a modest rise, on which besiegers of Vienna used to place cannon to bombard the city walls just below.

We walked around a lot. And I did fall for the place (again). No operetta, please, but .... The approach to things here, which is at worst lightweight and maudlin, has at best a marvelous lightness of touch, which Berlin does not have.

For example. Here's some of the neo-baroque (1901) sculpture on a militarist monument in Berlin, solemn and dopey. (In case this was not obvious to you, what you see here is an allegorical representation of the Power of the State Subduing the Leopard of Discord. I go past this all the time, it's more or less in our back yard.)

|

| Germania, Bismarck monument. Berlin. Photo by Taxiarchos288, Wiki Commons. |

Here's some of the neo-baroque (1897) sculpture on a militarist monument in Vienna--one of two fountains at the Hofburg honoring Austria's army and navy. (You might expect the Austrian navy fountain to be the more comic of the two, given that Austria has only intermittently possessed a coastline; but it isn't.) Compared to the Berlin work, it's lighter, almost witty.

|

| Detail from "Austria's Power on Land" fountain, Vienna. Photo, M. Seadle |

Vienna is a bit fantastic, full of fantasy, in ways that Berlin is not. Berlin has some fine, architecturally distinguished public housing, but nothing quite like this:

|

| Hundertwasserhaus, Vienna. Photo byMartin Abegglen, Wiki Commons. |

This piece of the Viennese public housing system is one of the Austrian artist Friedenreich Hundertwasser's joyful fantasy-buildings, what he called "houses for people and trees," bursting with greenery and color.

|

| Hundertwasserhaus, Vienna. Photo by Trishhh, Wiki Commons. |

Several years ago we stumbled across another Hundertwasser building, a high school in Wittenberg--which is an entertaining building, but isn't it a bit stiffer and heavier and colder than the apartments in Vienna?

|

| Luther-Melanchton-Gymnasium, Wittenberg. Photo by Grahamec, Wiki Commons. |

Wittenberg isn't Vienna. Wittenberg (soberly Saxon) isn't full of things like this (from the streets near the Hundertwasserhaus in Vienna)--

|

| Photo, M. Seadle |

Or, further afield, this street-railway station by Otto Wagner, with a glitter of gold at the top and a frieze of sunflowers:

|

| Otto Wagner, Stadtbahnstation Karlsplatz, Vienna. Photo, M. Seadle |

|

| Photo, M. Seadle. |

Vienna Magic--well, yes. Sleight-of-hand, illusion, offered in plenty here.

The core of the city, just below our place on the Spittelberg, is the Hofburg. This is a sprawling pile of palaces: seven centuries' worth of building, a seat of government, two churches, a major library, and so forth and so forth, covering over two million square feet. This is one corner of it, and it goes on and on and on, down the streets, down the centuries.

|

| Hofburg, Vienna. Photo by Windschatten, Wiki Commons. |

The Austrian National Library is in the Hofburg, and this is the library's Prunksaal--hmm, how to translate Prunksaal? Splendid room, grandiose room, pompous room? The first time I was here, back in the 70s, when I was pretending to be a historian, I spent most of my time working here--in the non-splendid, non-grandiose, non-pompous back rooms, but you could come through this way en route to serious work. (Does your local public library entrance look like this?)

|

| Prunksaal, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Photo, Manfred Morgner, Wiki Commons. |

The Hofburg is a big hat that has had a lot of rabbits coming out of it over the years. It's drenched in the Habsburg mythos, the dream of the universal absolutist state, melded with a universal church. In this dream, Vienna is the new Rome, the center of the universal empire ruled by a semi-sacred emperor. (Not a good rabbit, really.)

Presenting the universal-holy-empire notion obviously required a lot of Prunk. It also required a certain amount of fakery. For centuries the belief in Austria's special status was based on a document called the Privilegium maius, which surfaced in the fourteenth century and included various supposedly ancient grants of independence and superiority to Austria. The first of of the grants was given in a letter from Julius Caesar and the second in a letter from Nero.... Oh, right. Even in the fourteenth century, a good classical scholar like Petrarch could look at these letters and say, Fake! But the full scale of the forgery wasn't proved till the nineteenth century, and meanwhile it became the law of the land.

And yet--illusion time--one curious thing about this Viennese claim to universal absolutist empire is that often there wasn't any power at the center of power; somehow it evanesced away, there wasn't anything in the hat. Think how long, in the nineteenth century, in a so-called absolute monarchy, the absolute monarch (Ferdinand I) was incapacitated, incapable of rule (severely epileptic, possibly schizophrenic, troubled with difficulties speaking, and so on). Rabbits appeared to come out of the Hofburg hat: there were of course advisors, who told the emperor what papers to sign. But there were limits, somewhere, to the advisors' power. None of them, for example, could become emperor; and although they took strong measures to try to keep things as they were, perhaps there wasn't much that they could change. Hermann Broch wrote about Vienna in the late days of the empire: A dream, the city was, but the dream within the dream was the emperor ...

Ferdinand the incapacitated was officially the ruler for thirteen years, until the revolutions of 1848 made it seem wise to have some more presentable person as ruling emperor. Ferdinand kept the title but withdrew to Prague, where his also-schizophrenic ancestor Rudolf II had withdrawn, to be alone, to cultivate the sciences, to buy pictures, which ended up in Vienna rather than Prague.

|

| Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo, M. Seadle |

Ach, these pictures that Rudolf bought. I was so swept away by these when I first saw them in the 70s. You step into the room in the Kunsthistorisches Museum (sort of an outlier of the Hofburg) that's packed with Bruegels, and you think: But I know this country, I have been here in dreams.

You haven't, of course. Illusion, artistic sleight-of-hand. But they do look like places where you were once, where you thoughtlessly left part of yourself behind; and you feel as though you ought to go back and retrieve it. Into the painting, into the painting.

You haven't, of course. Illusion, artistic sleight-of-hand. But they do look like places where you were once, where you thoughtlessly left part of yourself behind; and you feel as though you ought to go back and retrieve it. Into the painting, into the painting.

Perhaps Rudolf the schizophrenic thought so too. Or perhaps the pictures looked altogether different to him than they do to us--who can say?

|

| Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Return of the Herd. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo, M. Seadle |

Rudolf's mental health problems and his unwillingness to play the role of war-leader against the advancing Turks in the sixteenth century eventually made him impossible as an emperor, and his brothers deposed him. But what then?

There's the potential candidate who turns down the opportunity because he likes his comforts and doesn't want the extra work and risk of the position. (This is Rudolf's brother Max, who won't do anything against the invading Turks because the food on military campaigns isn't very good.)

Then there's the candidate who really wants the job but is going to be a dud and has no idea that he is going to be a dud. (This is Rudolf's brother Matthias, who charges off against the Turks, fulminating against Rudolf's indecisiveness, and makes a hapless mess of the campaign. In the play, Rudolf says of Matthias, Neither of us inherited from our father the necessary drive to great deeds. Only I know it and he doesn't.)

And then there's the candidate who is truly capable and energetic--and who wants to take you in a direction in which it would be so very good not to go. (This is Rudolf's ambitious, capable nephew Ferdinand, who is something of a religious fanatic and is bent on wiping out Protestants.)

Pick your poison here. What is non-illusory? Max's view that war is a bad idea? Matthias' view that Rudolf is a hopeless mess and he himself is not? Ferdinand's view that both Matthias and Rudolf are hopeless messes, and that it's necessary to create a strong state by killing a lot of people?

Rudolf says, when asked why he spends his time with the sciences and not with political dispatches, says: In the stars there is truth, in stones and plants and animals and trees. But not in human beings.

**

The various failings of Rudolf and Matthias (who becomes emperor after Rudolf) and Ferdinand (who becomes emperor after Matthias) help to set off a gruesome, African-civil-war-like conflict that lasts thirty years and depopulates substantial portions of Central Europe.

But things change, things change. Eventually, after the war, Central Europe recovers. After a generation or two, it builds palaces and gardens again. Here is the splendid, grandiose, pompous Upper Belvedere, built in the 1720s for Prince Eugen, who had led the post-Thirty-Years'-War campaigns that drove the Turks back decisively, permanently out of Austrian territory, out of Hungary, out of parts of the Balkans, which then became Austrian territory. (Not in some ways a good idea, historically. Austrians in the Balkans will set off World War I. But who knows, in 1720?)

|

| Belvedere Palace, Vienna. Photo by M. Seadle. |

Prince Eugen didn't live up here, for the most part, the Upper Belvedere was just Prunk to make his power visible--though art historians note that one of the fine things about the building is that it's not just a solid massive block, as many palaces of the time were. Instead, it sort of thins out and evanesces away irregularly at the top. An image of power that fades at the edges, vanishes finally into nothing.

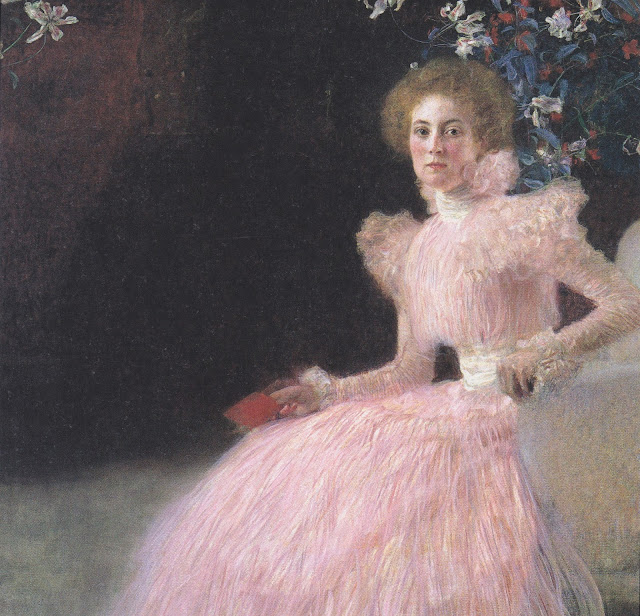

The Belvedere is a museum now, full of dreamy illusionary stuff from a century after Prince Eugen. Lots of 1900-ish women as marvelous luxury objects:

|

| Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fritza Riedel, Belvedere. Photo, M. Seadle. |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Sonja Knips. Photo, Wiki Commons. |

After a generation or so of all this glitter, Central Europe comes near to destroying itself again. A year into World War I, bodies start to look different to the artists:

|

| Egon Schiele, Death and the Maiden, Belvedere. Photo, M. Seadle. |

By 1918 it's all over, and a lot is over on the home front as well. Klimt, of the glittering young women, dies of a stroke at the beginning of 1918. Otto Wagner, of the sunflower-bedecked train stations, dies of more or less natural causes a little later in the year: he's well enough off, but he has refused to buy extra food on the black market, and sticking to the starvation diet you can get with your ration card, on principle, is maybe too much for an old man. Schiele, who is still young, dies of the flu epidemic that kills some fifty to a hundred million of the world's war-weakened population that year.

**

Well, it's all past, for the time being; and people sensibly beflower their balconies while the good times last. We are headed north, to Moravia and Silesia, places from which the Austrian and Prussian empires receded in the last century, leaving ... well, we will see.

|

| Photo, M. Seadle. |