February was time for some disorderly late-winter wanderings through the lake- and fen-land in southwestern Berlin, in the long glacial scoop-out that runs down the side of the city. This is not so much "walk by the water" as "walk some considerable distance from the water because the shores are private property"--but it's an interesting neighborhood.

Today we're working along part of the little tributary valley that runs east-west to meet the north-south valley of the main Grunewald lake-chain. We start at Heidelberger Platz, about halfway along the little tributary: the streetier half of it is better for today, in the wet and cold, and we'll do the parkier half when it's really spring.

The U-Bahn station at Heidelberger Platz is more than a little grand:

|

| Heidelberger Platz U-Bahn station. Photo, Stadtlichtpunkte, Wiki Commons. |

We are getting down toward grand-land here, toward the old Nobelviertel with the ambassadors' residences and such. We aren't quite there yet, but already here at the station there's a flavor of the manic historicism of 1900-ish building in these parts. (Let us build big Roman railroad stations! Let us build big Byzantine banks, let us build big Venetian villas!)

Here are the gates at the foot of the stairs, as we leave the station and head up into the late-winter drizzle:

|

| Heidelberger Platz station gates. February 2016, my photo. |

The historicist architects who built this kind of thing in Berlin in the half-century or so before World War I don't get a lot of love in more recent times. Who even knows, these days, who Franz Schwechten was, let alone who Wilhelm Leitgebel was? These are lost names. (And there are some good reasons for not admiring them. There's too much bloat in the buildings--they're big lumpy swaggering things that no longer strike us as beautiful). But these people gave a certain feel and flavor to the city: Berlin without fat historicism would be like curry without coriander.

Leitgebel built this U-Bahn station at Heidelberger Platz, and built the next one as well, Rüdesheimer Platz, also with ornate iron gates, just before the First World War.

|

| Ironwork at U-Bahn station Rüdesheimer Platz. Photo, JCornelius, Wiki Commons. |

The war pretty much put an end to the lush replication of historical styles in architecture in these parts. It also pretty much put an end to ornament (especially naturalistic ornament) on buildings. Starkness and abstraction set in. (Does this really make sense? Slaughtering fifteen or twenty million people means that we can't represent vegetation in the subway stations any more?)

It's partly guilt by association, of course. Fat historicism was the dominant style of the dominating class in Germany before the war, and these folks seemed utterly bankrupt--politically and intellectually and artistically as well as economically--by 1919. 'Tis well that an old age is out,/ And time to begin a new, as people always say after slaughters. (The lines are Dryden's celebration of the end of the murderous seventeenth century.) Time for white concrete cubes and the like, in the streetscape.

The guilt by association isn't entirely unfair. Fat historicism kept some bad company in Germany. Gothic revival, for example, gets carried along on different political currents here than in the Anglo-American world. English neogothic architecture carries with it a breath of Ruskin's and Morris's utopian socialism; model workers' housing in England can be neogothic. But socialist neogothic is not so likely here, where medieval architectural styles were kidnapped by aggressive, conservative nationalism.

Here at Heidelberger Platz we're on the edge of a neighborhood called the Rheingauviertel, named for the Rheingau wine region in Hesse; the street and square names are names of villages with well-known vineyards. (If you're a Riesling drinker, the names should sound familiar: Rüdesheim, Johannisberg). This is not altogether about innocent joy in good wine, however. I think that the (numerous) quarters in Berlin that were developed in the later nineteenth century and named for other parts of Germany were in part declarations of national connectedness, declarations that Berlin was the capital of all these places. (Not an uncontroversial statement, in the days when Germany as a national state was new.)

Thus there's some nationalist aggressiveness stirred into the good wine; and especially as we get closer to the turn of the century, the historicist style gets to be kind of a bad drunk. (It's loud and rude, it talks tastelessly about money and power.)

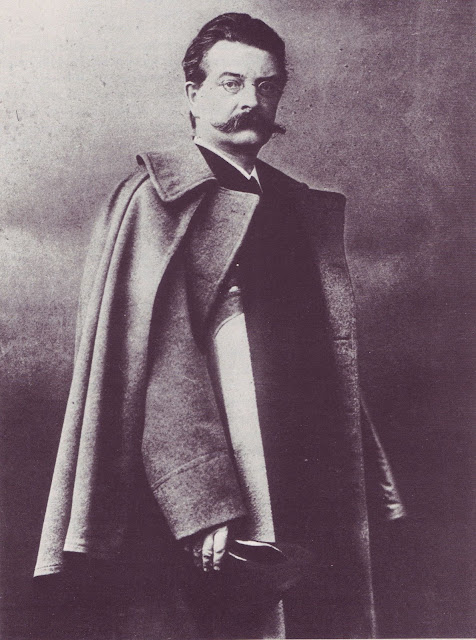

You can sort of get the tone of the time from looking at Franz Schwechten, who was a big-time historicist architect in Berlin in the decades before WW I. A bit overbearing in style, perhaps.

|

| Franz Schwechten, about 1895. Photo, Wiki Commons. |

Schwechten, whose name is largely forgotten these days, built major Berlin landmarks. He built the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtnis-Kirche, the church on Kurfürstendamm that was left as an iconic semi-ruin after WW II, as a warning against wars. He built the dopey tower in Grunewald in honor of Wilhelm I (see Havel 4 post from last summer). He built the ex-brewery in Prenzlauer Berg, the Kulturbrauerei, that in these days is stuffed with clubs and theaters and such and is a big gathering-place for the young. Schwechten also built the wildly Gothic part of our local power plant in Moabit (see Berlin-Spandauer Schiffahrtskanal 2 post). (Don't you feel that your neighborhood power plant needs a Gothic turret or two?)

Ah well, up the steps we go from the U-Bahn station, to the more brutal beauties of the postwar city. (I love the Berlin power plants, including ones like this--but surely the freeways are esthetically unredeemable?)

|

| Kraftwerk Berlin-Wilmersdorf and highway. Photo, Dieter Brügmann, Wiki Commons. |

Then we are past the freeway, into one of those non-grand little scraggles of city that are left over from highway-building, like scraps of fabric left when you've cut out an odd shape like a sleeve or a collar from a length of fabric.

Here is vacant land, fenced-off land of uncertain uses. Among the simpler graffiti someone has painted a woman with a bandage over her mouth and the legend, "She does not have the courage of her opinions."

|

| Near Heidelberger Platz. February 2016, my photo. |

Well, me either, much of the time.

In the course of development, some stretches of the tunnel valleys out here were drained and filled in, while others were deepened to gather the waters and turn them from seasonal damp spots to year-round lakes. Here is an oddity, an apparently unnamed, somewhat seasonal pool, an unreconstructed stretch of low ground along Forckenbeckstrasse that collects excess water when there are heavy rains. It stands behind the big Wilmersdorf Secondary School, in a way that is in principle handsome ....

|

| Wilmersdorfer Sekundarschule and pond, Forckenbeckstrasse. February 2016, my photo. |

... but mein Gott, this place is filthy. How trash-strewn the water's edge is, what dubious and rotting objects float in the water. Where is Max von Forckenbeck when we need him?

He gets a street named after him because he was the Oberbürgermeister of Berlin for fourteen years, beginning in 1878, and would have held the office longer if he had not died of pneumonia in 1892. Berlin was in its wild weedy industrial growth period then, with more people coming in from the poor countryside than the city could hold; insanitary shantytowns were crammed into the dank edges of the city. (Think Rio, think Delhi, though on a smaller scale.) Forckenbeck built sewers and schools, and transit and clean water supply and park space, and more sewers and more schools and more transit, and did it without making a mess of the city finances. A good man, Forckenbeck.

As we go round the west end of this body of water, this rotting corpse of water, the path through the trees climbs toward something dark and angular:

|

| Path to back of Kreuzkirche. February 2016, my photo. |

It looks a little grim on such a shadowy winter day (terrible day for taking pictures, there's no light). But here's our alternative to historicist architecture, before classic modernism--the real white-cube stuff--comes along. This is Expressionist architecture, north-German brick Expressionism, which I had no idea existed until I started wandering around Berlin. (I thought Expressionism was all angry periodicals put together by young men and given titles like Storm and Action; I thought it was poems that invoke the end of the world ("the hat flies off the bourgeois's pointy head ... the trains fall off the bridges"), and Edvard Munch painting The Scream, and Alban Berg writing sex-death-and-dissonance operas. But an Expressionist church building?? This was news.)

I think the first time Archangel and I seriously paid attention to this kind of building was several years ago when we were in Hannover and fell somewhat in love with the Anzeiger Hochhaus, a 1920s newspaper building that was one of the first high-rises in Germany and has a terrific street-presence.

Here's a bit of the Anzeiger Hochhaus, with the dramatic outlines and the dark, prickly, twisting brickwork that is characteristic of these buildings.

|

| Anzeiger Hochhaus, Hannover. Photo, Carl Dransfeld, between 1928 and 1938.Wiki Commons. |

And here's the Kreuzkirche in Berlin, as we sneak up on it from behind, from the rotten pond. Also some dramatic shapes and zippy brickwork:

|

| Kreuzkirche, Berlin-Wilmersdorf. Photo, Manfred Brückels, Wiki Commons. |

|

| Kreuzkirche entryway. Photo, Mutter Erde, Wiki Commons. |

There's a dubious smell about a lot of the Expressionist work, as there is about the pond we have just passed. Fritz Höger, who was officially the architect of the Anzeiger Hochhaus in Hannover, got into various problems for plagiarism, including for the Hannover building, which is over-dependent on the design of an unsuccessful rival for the commission. Höger also is the nominal architect of a very striking Expressionist church in this neighborhood (Hohenzollernplatz) which is said to have been mostly designed by his junior in the office, Ossip Klarwein. (Klarwein was a Polish Jew whom Höger--an early and sincere Nazi--fired for being Jewish already in 1932, before there was any pressure to do so, since the Nazis were not yet in power. Klarwein had the good sense to get out to Palestine before worse things happened.)

Some of the other Expressionists, painters and poets (Emil Nolde, Gottfried Benn), were enthusiastic Nazis as well. Nazism appealed to their anti-modernism, their hatred of cities and machines; it appealed to their taste for violent feelings, their glorification of the manly Nordic world. After an initial flirtation with Expressionism, however, the Nazis didn't love them back; the Party sold off or burned their paintings and burned their books. The Nazis mostly left the architecture alone, however. (After all, it's harder to change or destroy a building than to burn a painting.)

... But dear me, we've wandered a little out of the straight path to the lakes here. (Getting past the freeway, being distracted by this and that, being reluctant to pull out the map to get it wet in this drizzle.) Here we are at Grieser Platz, which is a little farther north than we want to be.

|

| Europa macht Handstand, sculpture by Ernst Leonhardt, 1995. Grieser Platz. February 2016, my photo. |

A few streets further on, and we're into Grunewald--Grunewald the sub-district, not (yet) Grunewald the forest. Nobelviertel stuff from here on. No more big graffiti, no more jokey 1990's public sculpture.

Big, big old villas, ravingly historicist:

|

| Villa, Grunewald. February 2016, my photo. |

... mixed with clinically severe modernism. (The modernism is like a breath of fresh air in a room that's been shut up for too long--but if the whole city looked like this, it would be like living in the open in a perpetual cold wind.)

|

| On Caspar-Theyß-Strasse. February 2016, my photo. |

The street stirs together old and new styles, villas and apartments and commercial space. (Near the buildings in the pictures above is the most architecturally discreet auto-repair place I have ever seen.) The mix gives the neighborhood its peculiar flavor, a kind of sweet-and-tart tang, not like a mono-style residential suburb.

Here we come to Koenigsallee, which is sort of a main drag through the neighborhood. There should be a bus stop along here, which would be good to note for the future .... Aagh, it's a ravingly historicist bus stop:

|

| Departure for the hunt under Kurfürst Joachim II from Jagdschloss Grunewald. Mosaic on Koenigsallee. Photo by Axel Mauruszat, Wiki Commons. |

This mosaic represents the sixteenth-century Kurfürst (Elector) Joachim II heading out for the hunt from the Jagdschloss (hunting lodge, sort of) Grunewald. (The Jagdschloss is on one of the lakes in the Grunewald lake chain, and we will get to it some day when it stops raining. Preferably well into the spring, when the place is open so we can have a look at the sixteenth-century paintings inside; I think the place is closed during the winter.)

One of the paintings in the Jagdschloss is a closer look at Joachim II himself, a contemporary portrait without any sentimentalizing 1900ish cleanup. He looks more than a little dangerous.

He was, too. Debased the coinage, oppressed the merchants, confiscated property in the interests of his building and territorial-expansion projects, and loaded the country with debt. (His successor solved the debt problem in part by plundering the Jews in Brandenburg, expelling them and keeping their property.)

It's all clean and pretty in the mosaic, and we can grumble about that if we want to. But the mosaic is appealing as another example of the exuberant technical skills of 1900-ish Berlin. The mosaic was executed (not designed) by the firm of Puhl and Wagner in 1910, which had been busy putting an end to the millennium-long Italian lock on technically-high-quality mosaic production.

One of the paintings in the Jagdschloss is a closer look at Joachim II himself, a contemporary portrait without any sentimentalizing 1900ish cleanup. He looks more than a little dangerous.

|

| Joachim II of Brandenburg, by Lucas Cranach the Younger. Photo, Wiki Commons. |

He was, too. Debased the coinage, oppressed the merchants, confiscated property in the interests of his building and territorial-expansion projects, and loaded the country with debt. (His successor solved the debt problem in part by plundering the Jews in Brandenburg, expelling them and keeping their property.)

It's all clean and pretty in the mosaic, and we can grumble about that if we want to. But the mosaic is appealing as another example of the exuberant technical skills of 1900-ish Berlin. The mosaic was executed (not designed) by the firm of Puhl and Wagner in 1910, which had been busy putting an end to the millennium-long Italian lock on technically-high-quality mosaic production.

Mosaics were used to decorate the Berlin bridges in those days. A few of the bridge mosaics are still in situ, for example on the Oberbaumbrücke that crosses the Spree to link Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain [see Spree 5 post, June 2014]--this is also Puhl and Wagner work.

|

| Puhl & Wagner mosaic, Oberbaumbrücke. Photo, Andreas Steinhoff, Wiki Commons. |

The Departure for the Hunt mosaic at the bus stop used to be on a bridge in the neighborhood here (specifically, the Hohenzollerndammbrücke--which is a bit of a mouthful). The hunting scene was on one side of the bridge, and the Surrender of the City of Teltow was on the other side. (Perhaps a scene from the thirteenth-century Teltow War between Otto-with-the-Arrow and Heinrich the Illustrious? [see Teltowkanal 5 post, January 2015].) When the bridge on Hohenzollerndamm was replaced in the 1950s, the Teltow mosaic was destroyed, but the hunting scene was saved and slapped onto the side of the old folks' home here by the bus stop.

**

We're into big-villa territory here. Farther down Koenigsallee, early in the last century, was the home of Walter Rathenau, a big man in the German economy before and during World War I, and then a political figure--mostly a diplomat, trying to work down the international tensions that were still rocking the world off-balance for years after the war.

The Rathenaus ran AEG, the German equivalent of General Electric. Franz Schwechten, the historicist with the big mustache, did some building for AEG: this is the gateway to the AEG works in north-central Berlin:

But Walter Rathenau's personal tastes ran in a different direction: his villa--which he designed himself, for the most part--is soberly classical, in the tradition of early nineteenth-century Prussia. (No turrets, no gold, no mosaics: Rathenau was an admirer of the coolness, the spareness, the moderation of Schinkel's aristocratic Prussian country houses.)

Not everyone saw Rathenau as a legitimate inheritor of Prussian tradition, however. Just here, past the bus stop, there's a marker at the awkward intersection on Koenigsallee where Rathenau's chauffeur slowed down to make the turn one morning, and the car behind sped up, one of the occupants firing a machine gun into Rathenau's car and another tossing a grenade.

This was 1922, so this was the work of old-line right-wing extremists, not Nazis yet. The assassins' organization didn't like Jewish industrialists and was also hoping to prey on the country's fears, to set off a civil war, to pave the way for a military dictatorship. It didn't happen, not yet; the country kept its nerve, more or less, and got another ten years or so of quasi-peace. There's a street-side marker here at the site of the assassination; it looks stern in the wintry afternoon, and desolate, with moss eating away at the stone.

A little further down Koenigsallee, and we're at a bridge over the little canal that links the Herthasee and the Koenigssee. These aren't natural lakes, they were made for decoration and drainage when this area--once called the Round Fen--was drained for real estate development in the 1880s.

Just past the bridge is a massive piece of eclectic historicism, the Villa Walter (named for its otherwise-forgotten architect, Wilhelm Walter). This comes from a time and place much given to overfed architecture, and the Villa Walter is a great big lump of a building.

It's bursting with garlands and mythological figures and symbolic representations in stone: crowds of naked angels hold up the building's protrusions.

Latin mottos are everywhere, mostly in stone .... but there are some in gold at the bottom of this slather of mosaic in the gable. Architecture the mother of the arts is on the right. On the left is a line from Horace: Nil sine magno vita labore dedit mortalibus. Life gives nothing to mortals without great labor.

These mottos sound a little self-advertising, and they were probably so intended. Allegedly--I don't know how true these tales are--the house was commissioned by a Russian aristocrat around 1912, but it wasn't yet finished when WW I broke out and the commission went south. Walter decided to finish up the house, to live there himself and use it as a kind of calling card: see what I can do!

But then the world that cared for this kind of thing fell into slaughter and bankruptcy. When Walter finished the house in 1917, he had hopelessly overextended himself financially and saw no usable future. Even with great labor, life may not give you so much. He is said to have hanged himself in the tower.

These days the house belongs to the Rumanian Cultural Institute. You can come out here to learn Rumanian, if this task is high on your agenda, or to see Rumanian art, hear readings from Rumanian literature, and so on.

Farther down Koenigsallee there's a useful footpath called the Hasensprung that takes us back down to the water.

Hasensprung (like other place-names in this corner of the city) is a vineyard in the Rheingau. But literally the word means rabbit-leap, and there are a couple of rather defaced stone rabbits on the bridge that takes us across the water. Koenigssee on one side, demented-looking rabbits in the middle, Dianasee on the other side, in the silver-dark of the winter afternoon.

Then up we go, out of this little tributary tunnel-valley, to another street named after a Hessian vineyard, which will eventually take us round to the Grunewald S-Bahn station.

It's a nice walk, the villas have their charm. Mostly it's very well-kept along here, but at one point there's a startling derelict, fenced off and apparently abandoned. This is the Villa Noelle, built around 1900 in vaguely German-Renaissance style for Ernst Noelle, a trader in steel back in the boom times of German steel-making. After Noelle died in 1916, the property changed hands a number of times, more than once by foreclosure sales; in the latter part of the 1930s someone turned it into biggish upscale apartments.

The apartments were still occupied ten or twelve years ago, and perhaps more recently. There are still names on the doorbell-plate at the gate, but the gate is padlocked. The place has a scraggy haunted look, and the clock over the door has been stuck at 10:00 for years. Perhaps the property has fallen into some legal dispute or financial mess that the participants choose not to air in public; although there's a lot of information available on the past of the house from local websites and newspapers, there's a dead silence about the present.

At the side of the locked gateway there is a decorative iron plate let into the now moss-eaten stone, in the German tradition of putting proverbs on the walls. (I like this: why don't we paint or carve big proverbs on our houses in the US?) This one says, Wägen, wagen. Weigh--that is, consider--and then dare.

Think ... and then have the courage of your opinions, as the graffito near Heidelberger Platz says.

Another of the relief plates on the locked gate says, if I remember correctly, Entscheidung ist alles. Decision is everything.

Well, I don't know; the dereliction here gives an ironic surround to this kind of chest-thumping. But maybe in another ten years some oligarch will come along and restore the place and polish up the proverbs--like Herr Noelle, fancying his success as the result of his own thinking and daring and decision, and forgetting that it helps when history tosses you some softballs.

**

We're into big-villa territory here. Farther down Koenigsallee, early in the last century, was the home of Walter Rathenau, a big man in the German economy before and during World War I, and then a political figure--mostly a diplomat, trying to work down the international tensions that were still rocking the world off-balance for years after the war.

The Rathenaus ran AEG, the German equivalent of General Electric. Franz Schwechten, the historicist with the big mustache, did some building for AEG: this is the gateway to the AEG works in north-central Berlin:

|

| Gate to AEG works, Berlin. Photo by Ansgar Koreng, Wiki Commons. |

But Walter Rathenau's personal tastes ran in a different direction: his villa--which he designed himself, for the most part--is soberly classical, in the tradition of early nineteenth-century Prussia. (No turrets, no gold, no mosaics: Rathenau was an admirer of the coolness, the spareness, the moderation of Schinkel's aristocratic Prussian country houses.)

Not everyone saw Rathenau as a legitimate inheritor of Prussian tradition, however. Just here, past the bus stop, there's a marker at the awkward intersection on Koenigsallee where Rathenau's chauffeur slowed down to make the turn one morning, and the car behind sped up, one of the occupants firing a machine gun into Rathenau's car and another tossing a grenade.

This was 1922, so this was the work of old-line right-wing extremists, not Nazis yet. The assassins' organization didn't like Jewish industrialists and was also hoping to prey on the country's fears, to set off a civil war, to pave the way for a military dictatorship. It didn't happen, not yet; the country kept its nerve, more or less, and got another ten years or so of quasi-peace. There's a street-side marker here at the site of the assassination; it looks stern in the wintry afternoon, and desolate, with moss eating away at the stone.

|

| Walther-Rathenau-Denkmal, Koenigsallee. February 2016, my photo. |

A little further down Koenigsallee, and we're at a bridge over the little canal that links the Herthasee and the Koenigssee. These aren't natural lakes, they were made for decoration and drainage when this area--once called the Round Fen--was drained for real estate development in the 1880s.

|

| Koenigssee. February 2016, my photo. |

|

| Villa Walter. Photo, Lienhard Schulz, Wiki Commons. |

It's bursting with garlands and mythological figures and symbolic representations in stone: crowds of naked angels hold up the building's protrusions.

|

| Villa Walter. February 2016, my photo. |

Latin mottos are everywhere, mostly in stone .... but there are some in gold at the bottom of this slather of mosaic in the gable. Architecture the mother of the arts is on the right. On the left is a line from Horace: Nil sine magno vita labore dedit mortalibus. Life gives nothing to mortals without great labor.

|

| Villa Walter. February 2016, my photo. |

These mottos sound a little self-advertising, and they were probably so intended. Allegedly--I don't know how true these tales are--the house was commissioned by a Russian aristocrat around 1912, but it wasn't yet finished when WW I broke out and the commission went south. Walter decided to finish up the house, to live there himself and use it as a kind of calling card: see what I can do!

But then the world that cared for this kind of thing fell into slaughter and bankruptcy. When Walter finished the house in 1917, he had hopelessly overextended himself financially and saw no usable future. Even with great labor, life may not give you so much. He is said to have hanged himself in the tower.

These days the house belongs to the Rumanian Cultural Institute. You can come out here to learn Rumanian, if this task is high on your agenda, or to see Rumanian art, hear readings from Rumanian literature, and so on.

Farther down Koenigsallee there's a useful footpath called the Hasensprung that takes us back down to the water.

|

| Hasensprung. February 2016, my photo. |

Hasensprung (like other place-names in this corner of the city) is a vineyard in the Rheingau. But literally the word means rabbit-leap, and there are a couple of rather defaced stone rabbits on the bridge that takes us across the water. Koenigssee on one side, demented-looking rabbits in the middle, Dianasee on the other side, in the silver-dark of the winter afternoon.

|

| Koenigssee from Hasensprung bridge. February 2016, my photo. |

|

| Hasensprung bridge. February 2016, my photo. |

|

| Dianasee from Hasensprung bridge. February 2016, my photo. |

Then up we go, out of this little tributary tunnel-valley, to another street named after a Hessian vineyard, which will eventually take us round to the Grunewald S-Bahn station.

It's a nice walk, the villas have their charm. Mostly it's very well-kept along here, but at one point there's a startling derelict, fenced off and apparently abandoned. This is the Villa Noelle, built around 1900 in vaguely German-Renaissance style for Ernst Noelle, a trader in steel back in the boom times of German steel-making. After Noelle died in 1916, the property changed hands a number of times, more than once by foreclosure sales; in the latter part of the 1930s someone turned it into biggish upscale apartments.

|

| Villa Noelle. February 2016, my photo. |

The apartments were still occupied ten or twelve years ago, and perhaps more recently. There are still names on the doorbell-plate at the gate, but the gate is padlocked. The place has a scraggy haunted look, and the clock over the door has been stuck at 10:00 for years. Perhaps the property has fallen into some legal dispute or financial mess that the participants choose not to air in public; although there's a lot of information available on the past of the house from local websites and newspapers, there's a dead silence about the present.

At the side of the locked gateway there is a decorative iron plate let into the now moss-eaten stone, in the German tradition of putting proverbs on the walls. (I like this: why don't we paint or carve big proverbs on our houses in the US?) This one says, Wägen, wagen. Weigh--that is, consider--and then dare.

|

| Gate relief on Winkler Strasse. February 2016, my photo. |

Think ... and then have the courage of your opinions, as the graffito near Heidelberger Platz says.

Another of the relief plates on the locked gate says, if I remember correctly, Entscheidung ist alles. Decision is everything.

Well, I don't know; the dereliction here gives an ironic surround to this kind of chest-thumping. But maybe in another ten years some oligarch will come along and restore the place and polish up the proverbs--like Herr Noelle, fancying his success as the result of his own thinking and daring and decision, and forgetting that it helps when history tosses you some softballs.